Our New Saint: John Henry Newman

“I ask not to see — I ask not to know—I ask simply to be used.”

At Belmont we have celebrated as Pope Francis created a new saint for the Church in England, John Henry Newman. On the weekend of the Canonisation the permanent deacons from the Archdiocese of Birmingham with with us on retreat.

It gives us pause to ask of this canonization, why Newman? What is his greatness? Is it as his insights as a teacher or warmth and humanity as a pastor? Is it as a man of courage seeking the truth at personal cost? Is it as a man of great friendships, who even at the painful parting of friends, maintained great affection for those he left behind. In his own words he wished to be “a link in a chain, a bond of connexion between persons…. an angel of peace, a preacher of truth in my own place.” He was all those things and much more.

Writing in the Osservatore Romano in a generous tribute to the new saint, Prince Charles praised the way Newman respectfully engaged in public and private debate: "In the age when he lived, Newman stood for the life of the spirit against the forces that would debase human dignity and human destiny. In the age in which he attains sainthood, his example is needed more than ever – for the manner in which, at his best, he could advocate without accusation, could disagree without disrespect and, perhaps most of all, could see differences as places of encounter rather than exclusion." He also praised his theology as an Anglican and as a Catholic for its “fearless honesty, its unsparing rigour and its originality of thought.”

What is the originality of his thought, and why might people be talking about him being not just a saint, but a new Doctor of the Church? Why is he considered an early father of the Second Vatican Council?

As an Anglican priest-scholar he dug deep into the tradition of the

church, with reverence for the Word of God, and its great interpreters, the

Fathers of the Church. But as he came to believe that “to be deep in history is

to cease to be Protestant" he could only seek communion with the

Catholic Church, led by the "kindly light" of the Holy Spirit. And as he searched

for the truth he proposed not new things, but uncovered eternal truths that had

been half forgotten and made them shine again.

What he found in the Church was not an antique shop of ancient treasures

to be nostalgically reverenced and guarded. What he found in the Church is a

living body walking in history, whose faith does not change, but whose expression

develops and deepens. We see new things. We see things better. The truths of

faith become clearer over time.

In Newman’s great work of historical theology, his Essay on the

Development of Christian Doctrine

,he would say that “to live is

to change and to be perfect is to have changed often.” Reflecting on this the then

Cardinal Ratzinger would say of himself: “precisely in changing, I have tried

to remain faithful to what I have always had at heart.” As Cardinal

Claudio Hummes remarked of Newman “it is by moving forwards that makes the

Church loyal to its true tradition.” Newman reminds us that the Church walks

in history. The

faith is dynamic. We are not antique dealers polishing the treasures of the

past. The church is not preserved in formaldehyde.

But

why did one English Roman Monsignor at the time of his conversion call him ‘the most

dangerous man in England.’ Partly because of his promotion of the laity whom

the Monsignor thought should stick to hunting, shooting and entertaining. The

laity are at the heart of the Church, Newman would reply, and kept the faith at

times in history when the bishops mislaid it.

“In

all times,” Newman insisted, “the laity have been the measure of the Catholic

spirit.”

Once

when discussing the laity, Archbishop Ullathorne scornfully asked Newman, “Who

are the laity?” Newman wrote in his

diary what he wished he had said in reply: “My Lord, the Church would look

rather foolish without them.” In a lecture on Catholics in England

he

said: “I want a laity, not arrogant, not rash in speech, not disputatious, but

men who know their religion, who enter into it, who know just where they stand…

who know their creed so well that they can give an account of it, who know so

much of history that they can defend it. I want an intelligent, well-instructed

laity…”

At

the end of Newman's life, Archbishop Ullathorne visited him, and when he was

leaving, Newman knelt at his feet and asked his blessing, saying that his own

poor work for the Church was as nothing compared to Ullathorne's. “I felt annihilated in his presence,” said

Ullathorne; “There is a saint in that man.”

Newman

prayed before the Blessed Sacrament: “I ask not to see — I ask not to know—I

ask simply to be used.” Just as he prayed not to see the distant scene, but

take the next step necessary. It is a prayer we can make our own

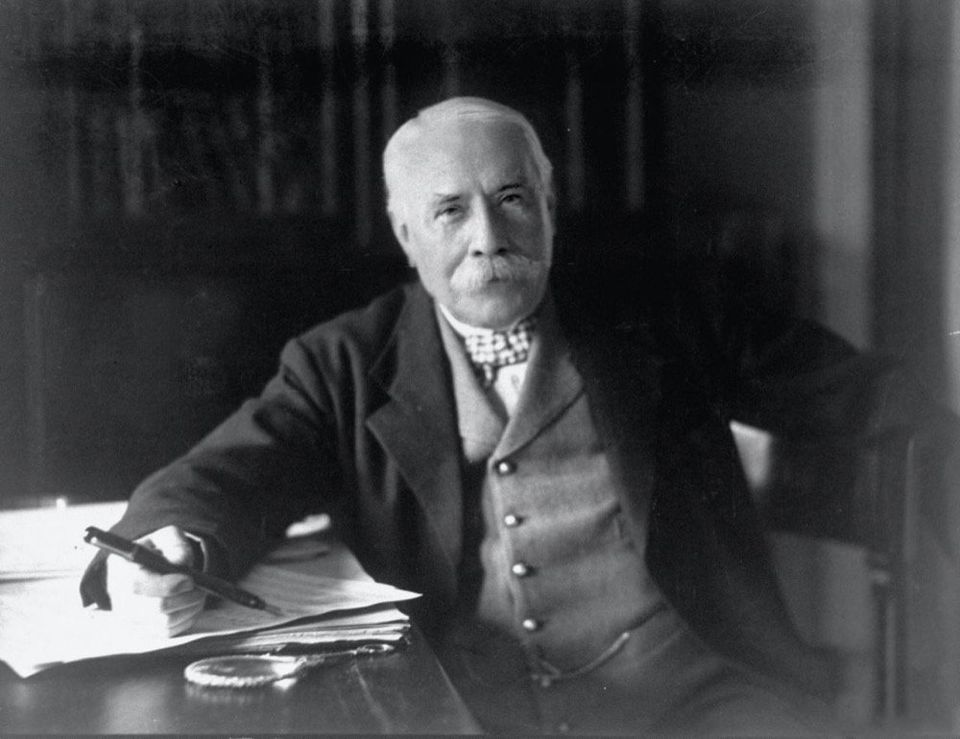

Sir Edward Elgar set Newman’s great poem The Dream of Gerontius

to

music. He occasionally came here to

worship in Belmont’s early years. In his diaries he records attending High Mass

one Sunday and remarks upon the music: “heard the monks sing the Song of the

Angel from the Dream of Gerontius.”

It is lovely to think that Elgar wove snatches of the monks’ singing into his setting of Newman’s great poem, their song adding melody to Newman’s Dream. Now as angel faces smile and rejoice in heaven at a new saint, we can echo their eternal hymn: “Praise to the Holiest in the height, and in the depth be praise. In all his words most wonderful, Most sure in all his ways.”