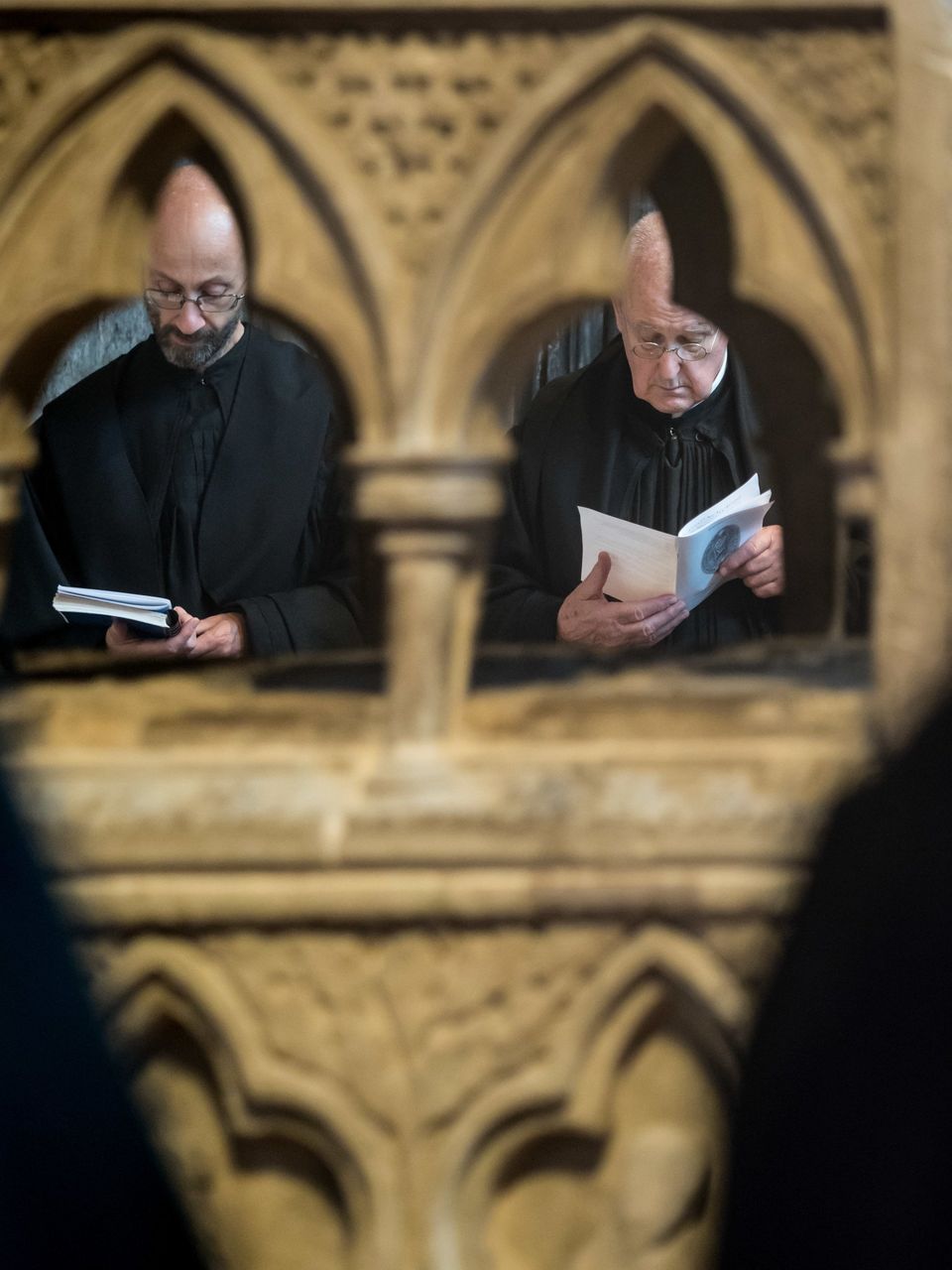

Vespers at Hereford Cathedral

It has become something of a tradition for the community to be invited by the Dean of Hereford to sing Vespers at the Cathedral for the feast of St Thomas Cantilupe. As always we had a warm welcome. Fr Brendan preached the sermon which is given below.

We know a little bit about his appearance of St Thomas of Hereford, his red hair and sometimes fiery temperament. We know the outlines of his life. How he was one of the great men of his age. A scholar – he studied in Paris, Orléans and Oxford in an academic career that spanned some thirty years. He became Chancellor of Oxford University, twice, Chancellor of the Realm and confidant of the King. We know that he was a reformist bishop, a supporter of the barons and the spirit of the Magna Carta.

All this is of interest to historians, but as Dom David Knowles has said, the thirteenth century is a period that keeps its own silence, an age in which we are given fewer insights to the inner lives of its outstanding personalities. We have, for example noone of St Thomas’s writings.

For centuries this Cathedral contained his bones, and pilgrims journeyed here to come into contact with a lunch-loved saint, a champion of justice, and in his death, miracle worker. Two years ago, as I was heading with a group of pilgrims to Siena, we made a brief detour to the monastery of San Severo, where shortly after his death, his flesh was buried as his bones were prepared to be sent back to England. Sadly because of the sharp corners of a windy road the coach was not able to stop and let us make our pilgrim stop. Perhaps it is a metaphor for how elusive Thomas of Hereford is to most of us. We know the bare bones of his life, as the people of Hereford revered his relics, but the fleshly saint remains more elusive. A man we can honour and admire, but today perhaps don’t know well enough to love.

We know quite a lot about his canonisation process which is quite revealing as to how the people of his day certainly loved and appreciated their saintly bishop.

I was reading recently a theory about how the “Frenchification” of the English language came about as a result of social snobbery. Part of the evidence of this was the canonisation process of St Thomas himself that took place in Hereford at the beginning of the 14th Century. The detailed records showed that of the 163 witnesses questioned most tried to speak in the most prestigious language they knew, like the friar in the Canterbury Tales who would throw in a bit of French to make it seem that he had class. E. F. Benson’s Lucia would do much the same thing in the small world of Tilling, slipping into la bella lingua at every given opportunity, or the social-climbing Hyacinth Bucket (surname pronounced in a French rather than down-to-earth Anglo-Saxon manner). In St Thomas’s beatification process, why use Welsh (only one witness did) when you can use English, but why use English when you can impress with French, and why use French when Latin, being the language of the Church, could outrank it on every occasion. (see: Jonathan Fruoco, New Chaucer Society Conference, July 2018).

Language is a fascinating thing. In a popular film and book the heroes have the very Anglo-Saxon sounding surnames Potter and Weasley, while the baddies have French-sounding aristocratic names like Voldemort and Malfoy. Anglo-Saxon suggests humility, French suggests entitlement.

Some of you may remember that old television sketch of John Cleese, Ronnie Barker and Ronnie Corbett. The tall Cleese in a bowler hat and pin-striped trousers looks down on Ronnie Barker and says “ I look down on him because I am upper-class.” The middle-class Ronnie Barker in a pork-pie hat and rain coat says “I look up to him because he is upper-class” ; but Ronnie Corbett in a cloth cap and muffler can only say: “I know my place. I look up to them both. I get a pain in the back of my neck.” And so the joke goes on about inferiority and superiority this class and social system that still today a source of merriment and pain.

It is hard to imagine that feudal structured world of Middle Ages. But the thing about St Thomas was that he wouldn’t look up to people with undue deference, nor down on others in disrespect. He would look people in the eye and tell the truth. In that sense maybe Thomas is saint for our age which is painfully learning to tell the truth about things. Women no longer looking up to media moguls or celebrities, unafraid to speak out. Victims unafraid to speak out about sexual abuse in the church, unafraid to look perpetrators and bishops in the eye. Ordinary people unafraid to challenge politicians and civil servants and say: this is wrong; this needs to change.

St Thomas would look his fellow bishops in the eye, as he did to the Archbishop of Canterbury John Pecham. He would look feudal barons, like Gilbert de Clare, in the eye and challenge their injustices. He was “conscientious, immune to bribery” as his biographer makes plain.

But most of all he looked the poor people of his diocese in the eye and told them of the love of Christ. He was known as a good shepherd to his flock, travelling around tending his churches, his clergy and flock: celebrating Mass, preaching, hearing confessions. The only major problem that he had in preaching to his diocese was that “ his vulgar tongue was Norman-French rather than English” so to get round the problem he would often be accompanied by his confessor who ‘was an excellent preacher in the English tongue.” So he responded the call of the Church of his day that would not stand aloof but would, as Pope Francis would say, know “the smell of the sheep.” He made sure that his flock would know their bishop and that they would be well-cared for. Like many popes, from Gregory the Great to Francis, he would have beggars sit at his table and eat with him. His biographer tells us that “the esteem he had [of the poor] was such that he commonly called them his Breethren (a name of greatest love)”.

As his biographer puts it: “This was the substantial part of his love to the poor, and he was not sparing of it: he had to witt, learned the great lesson of his Lord and Master, beatus est magis dare quam accipere , it is a more blessed thing to give than to take; and he was resolved to practice it in this behalf.” (Strange, Life and Gests, pp. 138-9)

Thomas became a saint for everyone, a man of independent mind. This is where we find his heart: with others , with victims of injustice, with the poor and needy. He came from a background of entitlement, but the only title he wanted was “Christian,” to be a disciple and servant of Jesus Christ. As Augustine of Hippo would tell his flock: “ For you I am a bishop, with you , after all, I am a Christian.” The role of bishop is one of service, to be a Christian is thing of grace.

So it is good for us to gather tonight to honour St Thomas. We too, Anglicans, Catholics and whoever we may be need to let go of our snobberies, and honour Christ best by being disciples together in and for the world. That would honour St Thomas best. It is good we pray together tonight.

St Thomas would have known the manual of pastoral care written by St Gregory the Great where he says: “The pastor must not only understand the mysteries of faith. He must live them. He must not be a fraud. If he is anything less, out of fear he should run from the office.” St Thomas did not need to run.

My favourite visual image of St Thomas is of him saying Mass. As he celebrated birds flew to the window at the sound of his voice. When he was silent they flew away, but as he began to sing again, back they came. How many people of this city came to hear his voice and loved him.