Poor Maggs: Belmont's Builder

“Poor Maggs Has Gone Off His Head” were words by Fr Cockshoot, clerk of works of the new monastery of St Michael's, that prompted Joanna Vials to dig deeper into the the rather sad story of Mr Austin Maggs, Belmont's builder.

Edward Welby Pugin, the architect, is a well-known name in the Abbey’s archives, but there is an intriguing passing reference in the contemporary records to the builder superintending the construction work in the 1850s. Fr Cockshoot, Clerk of Works for the Benedictines, commented in 1858, ‘Poor Maggs has gone off his head and has gone to the asylum.’ Since its start in mid-1857 the building work had progressed quickly but certainly not without problems. Fr Prest had been sent from Ampleforth to offer advice and, as early as September 1857, his report caused Fr Provincial Heptonstall to lament, ’Alas, that such blunders should have been made at the very commencement of Building and we the victims.’ Fr Ambrose Cotham OSB was called on to offer his opinion about ‘such blunders’; at this very time he was successfully raising the church of St Gregory the Great in Cheltenham with Charles Hansom as architect, and he had the experience of building two (small) churches in Tasmania. Despite financial and legal problems with his own builders no-one had actually ‘gone off his head’ in the process.

Pugin’s designs were elaborate – even grandiose – and there seems to have been confusion in his written specifications so that liability for early mistakes was not clear. Fr Heptonstall’s letter continued, ‘Maggs and not we must or at any rate ought to repair the blunder at his own expense and if these particulars … be not in the specifications then Pugin is very much to blame.’ However, these early technical problems were resolved and by the middle of 1858 at least 40 men were working on the site. Could the stress of work at St Michael’s have caused, or at least contributed to, Austin Maggs’ breakdown?

The case was widely reported in the local and national press and was carried by newspapers in France, Holland, the USA, and New Zealand. A short version of his case was given, for example in the Spectator for 5 May 1858:

Mr. Austin Maggs, an architect and builder residing at Hereford, has been arrested in consequence of having sent a letter to the Queen – calling upon her to render up to him her Majesty's office as Head of the Church. "Your Majesty will please to remember that this application is registered in Heaven, and will have to be accounted for at the judgment seat of our Lord. I shall be happy to produce to your Majesty my credentials as Christ's vice-gerent on earth." The unfortunate lunatic has been very violent while in the infirmary of Hereford Gaol. The Magistrates have remanded him, in order that his relatives may be communicated with.

Unsurprisingly, the fullest account was given in the Hereford Times on Saturday, 15 May 1858. The report covered the events which led to Maggs’ detention, and described at some length the background to it. Austin Maggs had successfully built up his own business from his premises in Old Market Street, Bristol. Most recently in the Hereford area he had worked as contractor for some extensive building operations in progress at the seat of Sir H G Cotterell Bart. MP at Garnons, in this county, but which, we understand, he relinquished before they were completed for want of the necessary funds to carry on the work. He was also the contractor for the Monastery for Benedictine monks in the course of erection at Belmont, near this city; but here too he got into difficulties that savour strongly of fraudulent intentions.

Looking at his circumstances it appears Maggs had over-reached himself, an almost inevitable consequence when small or medium size firms were engaged on large projects by a client hoping, or needing, to keep the cost down. Usually, neither client nor contractor had a large cash flow and payments were made piecemeal. Often small businesses grew through a process of temporary bankruptcy interspersed with securing lucrative contracts. But at this point in his professional career, the pressures of Austin Maggs’ personal life caught with him and he buckled under the strain.

Local press reports indicate the distress caused to Mr Maggs by his arrest. He had travelled to London to deliver his letter to Buckingham Palace and because he was considered a potential threat to Queen Victoria Sir Richard Mayne, chief of the London Metropolitan police, was informed. The possibility that he carried fire-arms led to him being ‘apprehended in bed’ at his lodgings in Broad Street at midnight. Perhaps unsurprisingly, despite being taken to the infirmary of Hereford gaol, he was ‘very violent, and broke the furniture and windows of the room’.

Poor Maggs had written courteously to the Queen as her ‘humble and loyal subject’, claiming to have credentials to prove his right to the throne, and showing her no ill-will.

In preferring my claim, your Majesty will please to observe, that it is from no sordid motive, but on the contrary, merely for the glory of God, the welfare of your Majesty's people, and the stability of your throne. Wishing your Majesty every happiness, both domestic and public, - I am, by the Grace of God, in your Majesty's service, AUSTIN MAGGS

It was quickly realised that Maggs was no threat to anyone and Sir Richard Mayne ordered that Austin should be given into the care of his brother and placed in an asylum; his brother was not surprised by the outcome and may even have been relieved to have the decision made for him by the court.

Austin Maggs might seem to have been a strange choice as superintendent builder for the monastery. However, he had successfully developed his building firm, employing ten men by 1851 when he was still only 30 years-old. E W Pugin was also a young man at the start of his independent career, and was another calculated risk. Ultimately the results were impressive although the work seemed to proceed by trial and error, the errors gradually becoming absorbed into the overall effect. After the court case in May 1858 the Hereford and Wiltshire Gazette suggested another theory, leaving it hanging in the air:

Maggs, when residing in Bristol was a member of a Baptist congregation; more recently, however, he showed a leaning toward the Roman Catholic religion, which was probably the cause of his being appointed to superintend the building of the monastery. His friends have long been aware of his inclination to insanity, and steps will be taken for his confinement in a lunatic asylum.

However, Austin Maggs’ private life had been troubled for some time. He wife of six years, Hannah, died from consumption early in 1851 leaving him with two daughters aged four and 10 months. His sister Sarah moved into the home at his premises in Old Market Street to look after the girls. The following year, Austin married Hannah’s elder sister, Elizabeth. Although the arrangement was not uncommon, there was a suggestion that his choice was connected with the money the women were able to bring into the business; their deceased father, Joseph Johnson, had been a respected silk merchant in Wells. In 1855 Maggs was still in a position to offer ‘constant employment and good wages to good workmen’ when he advertised, but when Elizabeth also died within a short time of her marriage, the loss was financial as well as personal.

Maggs’ family rallied round again but he looked for another advantageous match. Mistakenly, he pursued Miss Leonard, daughter of a very wealthy, and very upright Non-Conformist, Justice of the Peace, believing her to have affections for him. Robert Leonard of Clifton strongly objected, rousing Maggs to threaten to shoot him if he did not arrange the marriage. Austin was bound over to keep the peace, on sureties of £400 from himself and £200 from two other people, but his brother had already begun enquiries about finding an asylum for him. When he came to court in May 1858 the magistrate was led to believe that he had suffered a genuine ‘matrimonial disappointment’ and the £15,000 he expected to receive from his prospective bride would have salvaged his business speculations. This vain hope was undoubtedly another of Maggs’ delusions.

It may be that Maggs decided to move into lodgings in Hereford after the bad publicity in November 1857 connected with the JP’s daughter, especially if he was pinning his professional hopes on the commission for St Michael’s, Belmont, despite the early setbacks with the work. He was intending to auction in early February 1858 his three yards spread across sites at Old Market Street, Redcross Street, and Floating Dock, Bristol, together with timber, carts, counting-house fixtures and various doors, draining pipes and chimney pots. But even this decision brought yet another tragedy on him. In late January, the auctioneer, Vincent Scott, came to the yard in Old Market Street to arrange the sale; a pile of planks fell across his head and back and two days later he died of his injuries. The coroner concluded there was no malicious negligence in the yard and the death was an unfortunate accident. Austin Maggs, now 36, had already coped with a great deal in his life and only two months previously ‘his demeanour has been such as indicated an unsound state of mind.’ It was in this state that he was living alone in lodgings in Broad Street, Hereford. Although no details of his family were found in his lodgings when he was arrested, there was a letter in his coat pocket from his daughter, written from a boarding school in Bristol.

After the court cases in early summer 1858, Austin Maggs was given into the care of his brothers, James and Henry, although it was James who gave him lifelong support. After a brief spell in a private asylum in Church Stretton, then at Bethlehem in Caernarvonshire, and for a month at Camberwell House, London in October 1858, he was moved in November 1858 back to the West Country, to Bailbrook House, near Bath. The hope of finding a cure had probably given way to the realisation that long term care was needed. Whereas Camberwell House had accommodation for 500 patients, men and women, pauper and private, Bailbrook House sometimes had less than 40 residents, male and female, all privately financed. After two years, in November 1860, Austin was discharged, though ‘not improved’, but the release was short-lived. At the time of the census in early April 1861 he was again a resident, ‘A.M. Widw 38 Builder and Contractor, b. Somerset Midsomer Norton.’

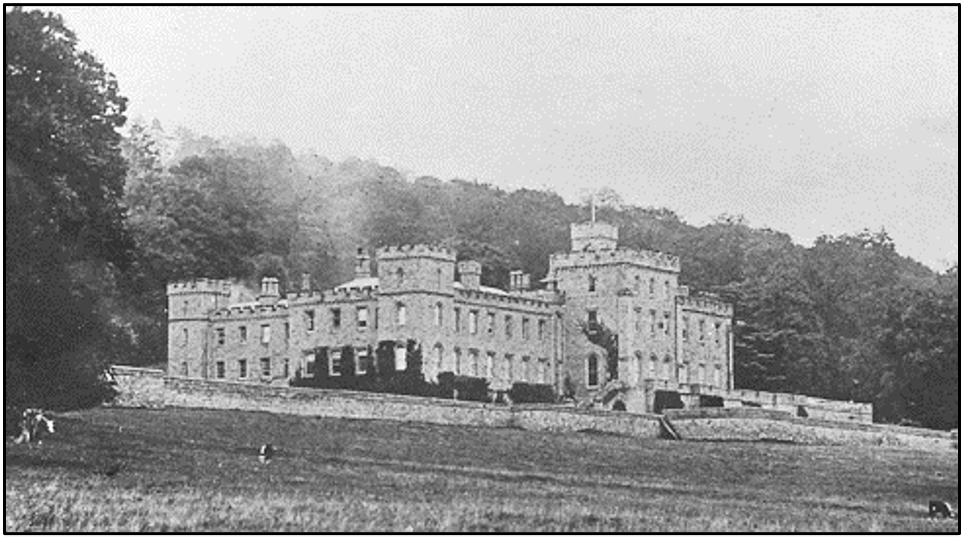

Bailbrook House, Batheaston (left) was an impressive 18th century mansion designed by Sir John Eveley. Between 1816 and 1821 it was an innovative benevolent institution for ‘distressed gentlewomen’. In 1831 it opened as a licensed Lunatic Asylum, but its character was defined by the long-lived superintendent-surgeon John Terry who spent most of his adult life as its head, succeeding his father as proprietor. His mother and sister, both named Matilda, lived separately and independently with him, but one imagines in sympathy with John’s regime.[John Ferry died in 1899, aged 77. He left £113,000 in his Will]. In 1861 Austin Maggs was one of 33 residents, 15 of them male. The age and professional range was wide: a 34 year-old clergyman curate lived alongside 70 year-old landowners and a brewer. Three live-in male and three female attendants looked after the residents with a general household staff of five women. Most of the residents were from the West Country, with a few from London or Ireland. Ironically, Austin’s delusions of being a claimant to the royal throne had taken him from the builder’s yard to the society of the relatively wealthy and genteel.

Maggs’ building premises and contents were finally auctioned in the summer of 1858, but too late to rescue his failed health and prospects. The responsibility for Austin’s welfare fell to his brothers. Henry (b.1828) may have helped financially as he developed his career as a carpet wholesaler, gradually moving north and settling with his family in Liverpool. But it was his brother James, together with their sister Sarah, who kept the family together. In 1861, James and Sarah were still living with their mother and Austin’s daughters, Ellen and Jane in their home town of Midsomer Norton. In the census years 1871, 1881 and 1891, James and Sarah, both unmarried, lived in Welton, Midsomer Norton, with their unmarried nieces. By the time he was 60 in 1861, James, formerly a mining engineer and blacksmith, was able to live as a gentleman ‘on his own means’ and support the family.

POSTSCRIPT

There is no way of knowing how much contact Austin had with his family after 1858. He was the first to die from their little group, in 1875, at the age of 53, leaving ‘effects under £100’ to his elder daughter, Ellen. When his brother James died in 1893 he left his estate of £1500 to his two nieces. Ellen died in 1900 at the age of 51, leaving £480 to her younger sister, Jane, and the following year Aunt Sarah died. Rather surprisingly she left her estate of £780 to Elizabeth Jane Walker Carter, a widow, nearer in age to the nieces, originally from Dundry, Somerset. However, Jane was registered as a visitor in Mrs Carter’s house in Gloucester at the time of the 1901 census, an arrangement probably made before Aunt Sarah’s death, to provide a home for the sole-survivor of James Maggs’ household. Even more surprisingly, in 1905 Jane married Elizabeth’s brother in Gloucester. She was 55, John Henry Walker was ten years older, and a successful farmer at Whittox End, Much Marcle. After his marriage, he and Jane continued to live with his unmarried sister and their niece – a family situation very familiar to Jane, though one hopes with happier memories.

Joanna Vials

Cheltenham, March 2021

Joanna Vials read Philosophy at the University of Warwick. After living for a time as a Carmelite nun at Quidenham, she took a Diploma in Pastoral Studies at Birmingham University and then followed a career as a relationship counsellor. Since settling in Cheltenham with her husband in 2007 she has researched the development of the presence of the Catholic Church in the town and she currently serves on the Committee of the Cheltenham Local History Society. Her book, The Indomitable Mr Cotham: Missioner, Convict Chaplain and Monk

was published in Jan 2019 by Gracewing.