Benedict's Genius

Monastic History in Glass and Stone (2)

How the Chapel of St Benedict, in its stained glass and carving tells us something of the whole history of Benedictine Monasticism, the importance of the English Church, and the place of Belmont in this story.

Watching over the whole Chapel of St Benedict, at the centre of the reredos , is the slender figure of the Saint himself. With one finger to his chin, the saint calls us to ponder the fastened copy of the Rule that he holds up in his other hand for all to see.

Benedict was very modest in his intention in writing his Rule . It was, he said, ‘a little Rule for beginners . ’ He didn’t intend to produce anything radically new; rather he sought to present a carefully balanced synthesis of the monastic tradition that had gone before him – a movement that was already considered old and venerable in Benedict’s day. With typical humility (Benedict not only taught it but practiced it) he sends his readers back to those first centuries of monasticism and to its great writers. There, he says, in Cassian, in Basil, in the lives of the Fathers we find the loftier heights of learning and virtue. Benedict’s Rule is not the beginning of the monastic story, but it would open a new chapter for the Western Church.

St Benedict didn’t intend his Rule to be particularly new or original. His genius lies in the way he drew on his sources and produced a document that is both sound and practical. He passes on to us the heritage of Saints Antony and Pachomius, Basil, Cassian and Augustine in distilled form. To the ideal of the individual pursuit of holiness under the guidance of a spiritual father (the tradition that comes from Egypt, through John Cassian and the Rule of the Master) Benedict added something of Augustine’s attention to the quality of human relationships and prioritising of love over asceticism.

The great monastic scholar Dom Adalbert de Vogüé has remarked that ‘the Rule of St Benedict begins in the desert of Egypt and ends in the City of Augustine’, a comment that reflects both the literary composition of the Rule with its changing emphasis, but it is also to be seen in the unfolding of Benedict’s own life.

Benedict took the best of these ancient traditions and added an important quality that his biographer Pope St Gregory the Great would highlight: discretion. He produced a Rule strong enough to lead his followers to the heights of virtue, flexible enough to withstand the vagaries of the centuries ahead, and compassionate enough to encourage the weak not to give up on their search for God. Benedict needed discretion and uncommon wisdom to be a true father to a seemingly rough lot of monks who could be stubborn, lazy and difficult.

There are two touching scenes in the reredos of St Benedict’s Chapel. They are key episodes from Benedict’s own life, yet capture something of the eremitical and cenobitical poles of monasticism.

In the first scene the young Benedict sits in his narrow cave at Subiaco, content as he was to pursue the solitary quest and live ‘alone with himself.’ He fixes his gaze towards the cross, as indeed he is portrayed in the original cave at Subiaco today.

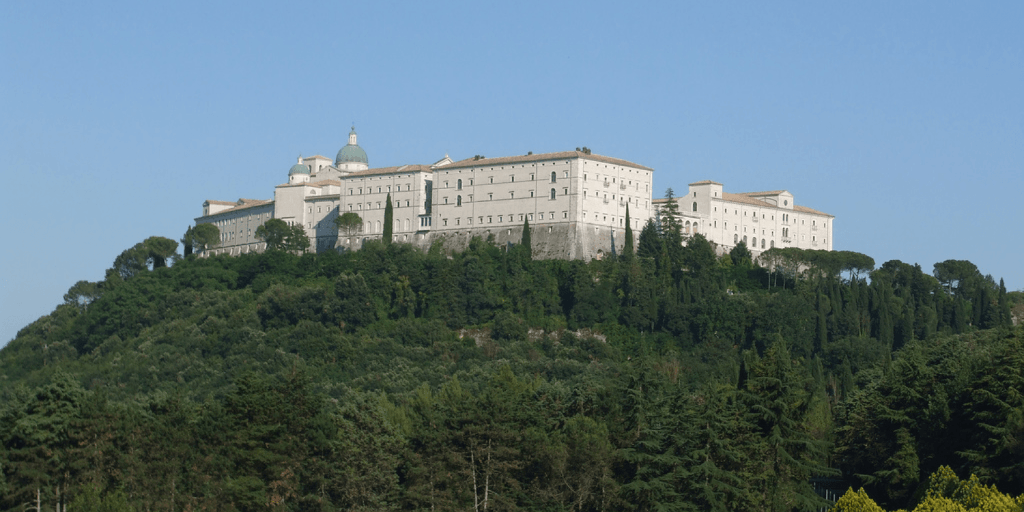

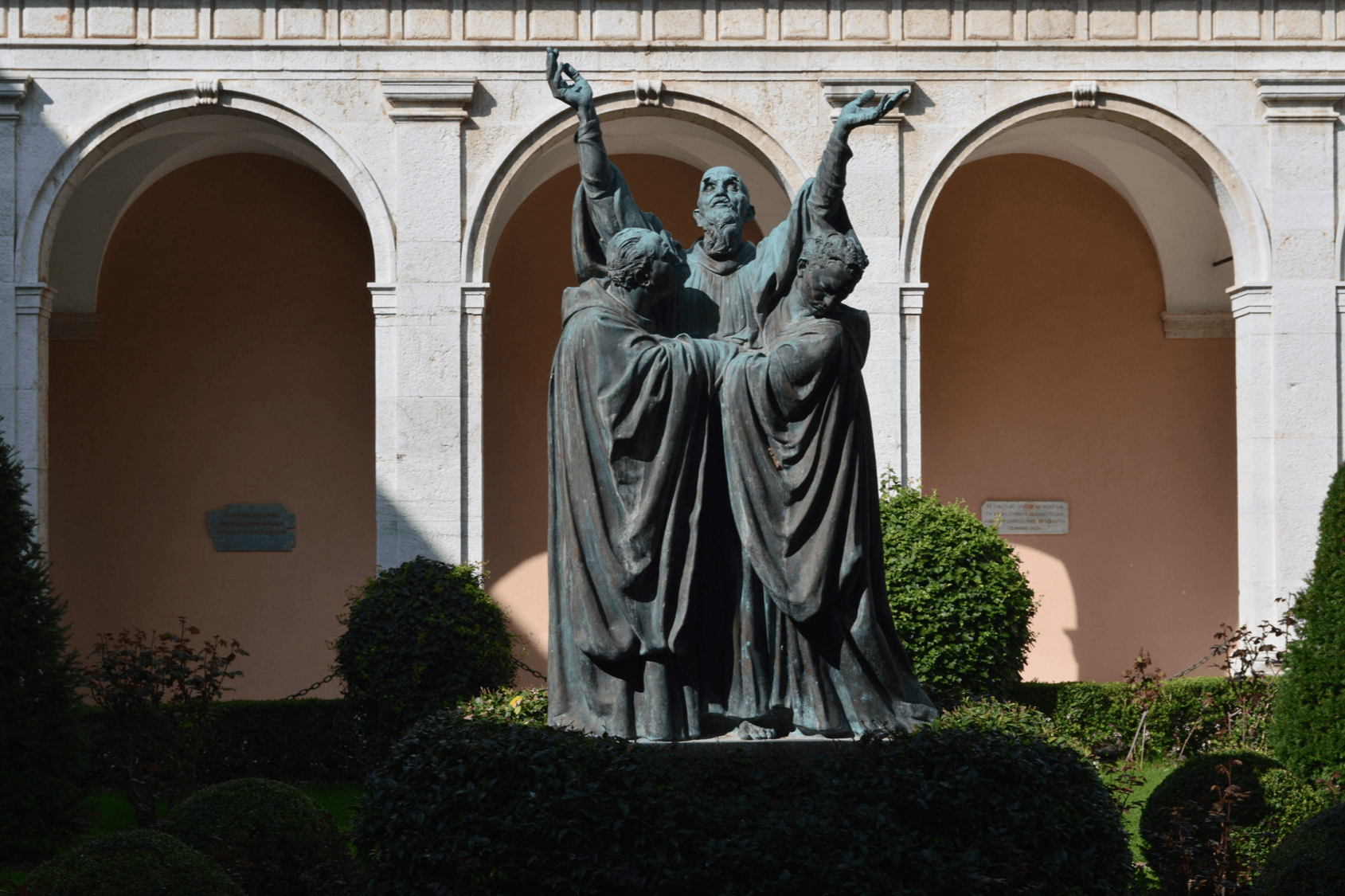

In the second scene we see the dying Benedict supported by his brethren, receiving Holy Communion in the little oratory of St Martin that he had built at Monte Cassino. This is a picture of what the cenobitical life has always been about: the brethren support each other in their quest for communion with God. Benedict, who had certainly experienced many trials with (and from) his brethren, is brought to the end of his monastic journey and into perfect communion with God only through the help and support of these same men. Through the good zeal of his own brothers, who had learnt to support his weaknesses, and through their humble love he is carried into everlasting life.

Saint Benedict was buried at Monte Cassino next to his twin sister Scholastica, where their tombs can be visited today. As we admire the stained-glass portrait of the Scholastica, clothed as she is in a rather elegant black habit with gold stars, we might remember that Benedict learnt the most important lesson of all from her: that love can do more than the greatest monastic observance and discipline. Her appearance in the story of Benedict is brief but powerful.